“Everything changed for me once I started talking.”

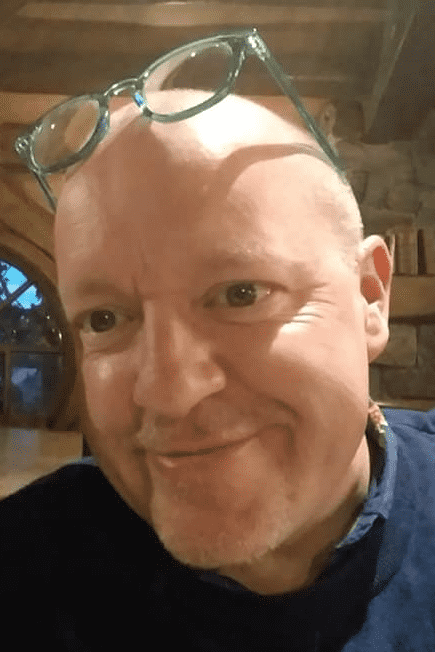

In the framework of our #ThisWay Campaign, the EHC interviewed Scott McLean (31) from the United Kingdom, a patient with severe haemophilia A, who shared with us how haemophilia impacted his mental health, how he went from denial to acceptance, and how you as a patient can also look after your mental health.

We hope you find Scott’s story inspirational. If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with Scott, please do not hesitate to drop us an email.

Scott McLean (31), United Kingdom

“I was diagnosed with severe haemophilia A when I was 8 months old. My mom took me to the hospital in Scotland after she spotted a bruise the size of a pea that grew to the size of a fist overnight. Prophylaxis only came around when I was at age 7-8 but I didn’t start doing my own injections until I was about 13-14 years old – before that, my mom didn’t want to leave it with me because she knew I wouldn’t do my injections. She held me back in looking after my condition, which didn’t help, considering that was the only control I had.

“I was diagnosed with severe haemophilia A when I was 8 months old. My mom took me to the hospital in Scotland after she spotted a bruise the size of a pea that grew to the size of a fist overnight. Prophylaxis only came around when I was at age 7-8 but I didn’t start doing my own injections until I was about 13-14 years old – before that, my mom didn’t want to leave it with me because she knew I wouldn’t do my injections. She held me back in looking after my condition, which didn’t help, considering that was the only control I had.

In school, everyone knew I was the kid with a bleeding disorder. I was seen as fragile and someone who could die from a papercut, which led to some bullying, and to make things worse, my cousin, who was in the same year in school tried to step in to protect me, thinking he was doing the right thing, but it made things worse because I became this person who couldn’t stand up for himself.

Around age 15-16, I decided to ‘quit having haemophilia’, not do my injections, and see how long I can go without having any bleeds. That lasted about 3 months to the point where I took a bad bleed into my hip and right leg and I couldn’t walk. I was in and out of the hospital, only being able to walk on crutches. It was at that point that it became clear to me that my not doing my injections can cause permanent joint damage further down the line, and that made me do my injections.

I didn’t like telling anyone about my condition because people thought I was fragile and made me feel alienated. I felt like I had something to prove. If someone said something to me, I would overreact, get into fights and bad situations to prove that I wasn’t this delicate person, which obviously wasn’t a healthy way to cope. Instead of being argumentative, I’d now try and educate someone.”

MINDSET

“The biggest issue was the lack of control. I felt like I was stuck with my condition, injections, physiotherapy, hospital appointments… It was a big turning point when my friends learned more about haemophilia and started to truly understand it, and made me feel more included. One day before going out with my friends, I didn’t want to do my injections so all of my friends grabbed a needle and stuck it in their veins and said: ‘We’ve all done our injections, you need to do yours as well.’

“The biggest issue was the lack of control. I felt like I was stuck with my condition, injections, physiotherapy, hospital appointments… It was a big turning point when my friends learned more about haemophilia and started to truly understand it, and made me feel more included. One day before going out with my friends, I didn’t want to do my injections so all of my friends grabbed a needle and stuck it in their veins and said: ‘We’ve all done our injections, you need to do yours as well.’

If I were to look at 16-year-old me, I wanted to have nothing to do with haemophilia. I did not want to acknowledge it; everyone bringing it up made me feel weak. Whereas now I’m an entirely different person. I’m in control of my condition. I used to think I was someone who suffered from haemophilia whereas now I’m someone who’s living with haemophilia.

My anger toward haemophilia came from being told I couldn’t do certain things. If you tell someone for long enough that they cannot do something, they’re not smart enough, they’re not strong enough, etc., then they’re going to believe it. With haemophilia, there’s an element of truth to that, but it’s not that black and white, especially not anymore with the treatment landscape we have. People can do so much more today than they could 20 years ago because of the therapies available. Personally, I’ve got tattoos, I’ve run a marathon, I’ve done a skydive…

The biggest element is understanding your bleeding disorder first, what works best for you in terms of treatment, and how you can personalise it based on what you want to be able to do. Once that’s in place, then it’s easier to communicate that to your friends, partners, and employer because the more they understand the better position they’re in to help you. People cannot help you if they don’t know what you’re going through. Everything changed for me once I started talking.”

BOTTOM LINE

“Your mental health is very much the same as your physical health: you can’t just expect to be mentally healthy, you have to work at it, and you have to train yourself. There’s nothing wrong with having difficult days but you need to put the work in to have your normal and happy days, and it’s about finding the right ways to do that for yourself, and it’s different for everyone.

Unfortunately, not everyone has the same social network as I do but what they do have is their community, their NMOs. Find people you can talk to, whether it’s people in your NMO, your doctor, or a licensed therapist. Lastly, get comfortable with your condition, get comfortable explaining it, be on top of your treatment regime and you’ll rarely have issues because you’re now in control of your bleeding disorder.”

Jim is aged 66 and has Haemophilia A with a high titer inhibitor which he developed at age 14.

Jim is aged 66 and has Haemophilia A with a high titer inhibitor which he developed at age 14. Maria Elisa Mancuso (MD, PhD) is a Haematologist and works as a Senior Haematology Consultant at the Center for Thrombosis and Haemorrhagic Diseases of IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital in Rozzano, Milan, Italy. She is Adjunct Clinical Professor at Humanitas University. She obtained a post-degree in Clinical and Experimental Haematology and a PhD in Clinical Methodology. She is involved in clinical research and has published several original articles in peer-reviewed journals a The Lancet, Blood, Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Haematologica, Thrombosis and Haemostasis, British Journal of Haematology and Haemophilia. She is reviewer for several peer-reviewed journals and member of the Editorial Board of JTH. She is a member of several scientific societies (ISTH, WFH, ASH, EAHAD, SISET, AICE) and was a medical member of the Inhibitor Working Group of the European Hemophilia Consortium. She is co-chair of the ADVANCE Study Group. She has acted also as co-chair of the Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee of ISTH on FVIII, FIX and rare bleeding disorders. She has been involved as principal and co-investigator in several clinical trials, and she takes care of both children and adults with hemophilia and other congenital bleeding disorders with a specific scientific interest in novel therapies, prophylaxis, inhibitors, and chronic hepatitis C.

Maria Elisa Mancuso (MD, PhD) is a Haematologist and works as a Senior Haematology Consultant at the Center for Thrombosis and Haemorrhagic Diseases of IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital in Rozzano, Milan, Italy. She is Adjunct Clinical Professor at Humanitas University. She obtained a post-degree in Clinical and Experimental Haematology and a PhD in Clinical Methodology. She is involved in clinical research and has published several original articles in peer-reviewed journals a The Lancet, Blood, Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Haematologica, Thrombosis and Haemostasis, British Journal of Haematology and Haemophilia. She is reviewer for several peer-reviewed journals and member of the Editorial Board of JTH. She is a member of several scientific societies (ISTH, WFH, ASH, EAHAD, SISET, AICE) and was a medical member of the Inhibitor Working Group of the European Hemophilia Consortium. She is co-chair of the ADVANCE Study Group. She has acted also as co-chair of the Scientific and Standardization Subcommittee of ISTH on FVIII, FIX and rare bleeding disorders. She has been involved as principal and co-investigator in several clinical trials, and she takes care of both children and adults with hemophilia and other congenital bleeding disorders with a specific scientific interest in novel therapies, prophylaxis, inhibitors, and chronic hepatitis C. As a patient with factor II deficiency, the diagnostic and treatment of rare bleeding disorders is a matter dear to my heart. My motivation to participate in the work of the ERIN committee is to improve both diagnostic and treatment for patients with rare bleeding disorders across Europe.

As a patient with factor II deficiency, the diagnostic and treatment of rare bleeding disorders is a matter dear to my heart. My motivation to participate in the work of the ERIN committee is to improve both diagnostic and treatment for patients with rare bleeding disorders across Europe. Economist and financial expert by profession, executive coach and trainer by passion and haemophilia advocate by every drop of my blood through my son (who has severe haemophilia A with inhibitors). Bringing a good decade of practical experience from the corporate insurance world, laser focus, growth mindset and resilience from my own experience, offering you anything I can just do, in hope that together we can make life more fulfilled for those impacted by bleeding disorders.

Economist and financial expert by profession, executive coach and trainer by passion and haemophilia advocate by every drop of my blood through my son (who has severe haemophilia A with inhibitors). Bringing a good decade of practical experience from the corporate insurance world, laser focus, growth mindset and resilience from my own experience, offering you anything I can just do, in hope that together we can make life more fulfilled for those impacted by bleeding disorders. Amy Owen-Wyard is a Registered Mental Health Nurse. With experience working with children, young people, their families and adults with severe and enduring mental health conditions. Amy was also involved in a service improvement to provide a holistic care approach for those in general hospitals to support both their mental and physical health, whilst sharing her expertise and knowledge in mental health with the wider multidisciplinary team.

Amy Owen-Wyard is a Registered Mental Health Nurse. With experience working with children, young people, their families and adults with severe and enduring mental health conditions. Amy was also involved in a service improvement to provide a holistic care approach for those in general hospitals to support both their mental and physical health, whilst sharing her expertise and knowledge in mental health with the wider multidisciplinary team.